19 February, 2026

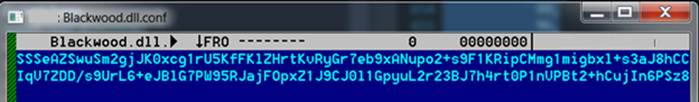

After successfully decoding the large static byte array in PrivateImplementationDetails in Part 1, we uncovered internal references to an encrypted configuration file: blackwood.dll.config (MD5: 03cffb8c4aa5113de6034fb82af529e6). This file is not embedded in the binary, but rather exists alongside the DLL on disk, and it contains runtime parameters essential to the malware’s operation. Unlike the obfuscation seen in the static byte array, this file is encrypted using the RC4 stream cipher and is loaded and decrypted dynamically during execution.

Thus, finding and opening the file in a live system would not be useful. Understanding how the malware decrypts this file is a key step in uncovering its operational logic without executing it.

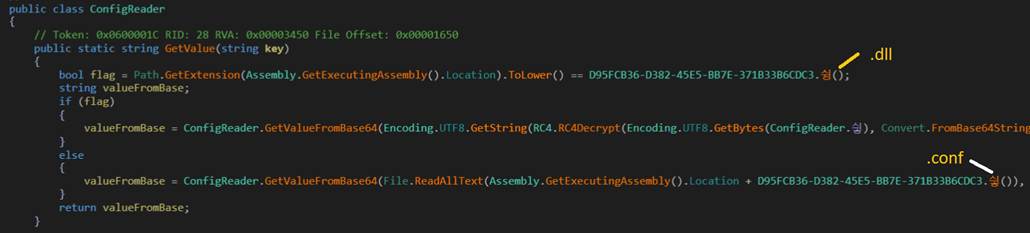

The file blackwood.dll.conf is accessed via the ConfigReader.GetValue() method. The logic starts with a simple check to determine whether the malware is running as a DLL.

Figure 1: Encrypted content of the config file

Figure 2: ConfigReader snippet

This line acts as a conditional gate, only if the current file extension ends in .dll will the RC4 decryption routine be executed. Otherwise, the malware skips decryption entirely.

To construct the path to the encrypted config file, the malware uses a helper method called 싛() which resolves the string ".conf". Combined with the executing file name (blackwood.dll), this results in blackwood.dll.conf. This .dll.conf naming scheme is critical as it avoids hardcoding the config file name anywhere in the file and ensures that the malware adapts dynamically based on how it's deployed. Without this exact file in the same directory, the decryption will fail.

If the .dll check passes, the code reads and decrypts the config as shown below:

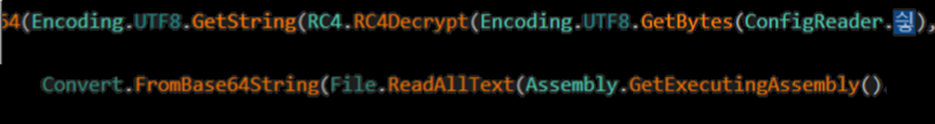

Figure 3: Decryption routine

Here’s what happens step by step:

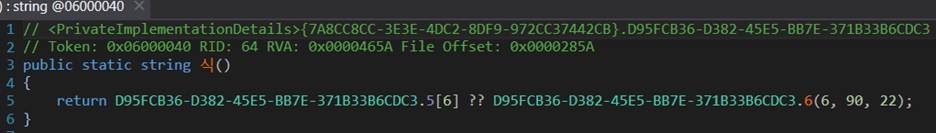

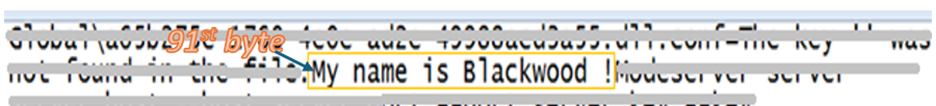

We traced a helper function call that returned the RC4 decryption key, which led us to the exact location of that key inside a large static byte array stored inside the PrivateImplementationDetails. The function call passed specific parameters (index = 90, count = 22) that pointed to the decryption key’s position. Because arrays in .NET are zero-based (meaning the first element has index 0, not 1), these parameters extracted 22 bytes starting from the 91st byte in the array. Now we know exactly the location of the RC4 key.

Figure 4: Snippet of the helper function referencing the RC4 key

Figure 5: RC4 key location

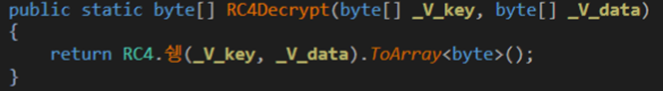

The final decryption is handled by the RC4Decrypt() method, which acts as a wrapper around the obfuscated RC4 routine. It takes the derived key and encrypted data as inputs, passes them to the underlying algorithm, and returns the decrypted bytes.

Figure 6: RC4Decrypt method

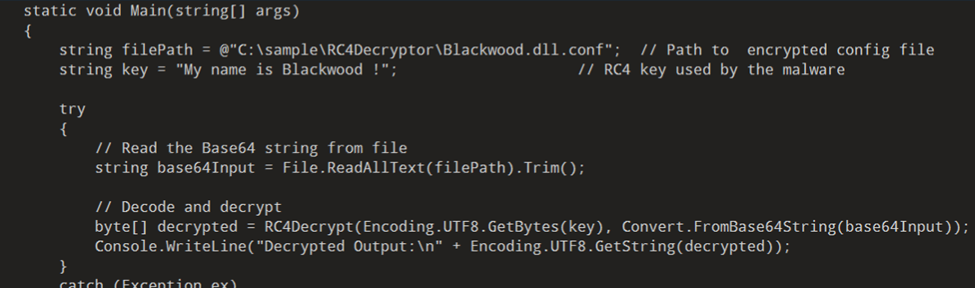

To validate our static analysis and test the decryption flow, we replicated the malware’s RC4 logic in a standalone script. As confirmed in earlier stages, the decryption key is derived from the decoded static byte array and is hardcoded as the string:

My name is Blackwood !

Using this key, we wrote a simple C# program to decrypt the base64-encoded configuration file. Here's a trimmed snippet of that program:

Figure 7: decryption code snippet

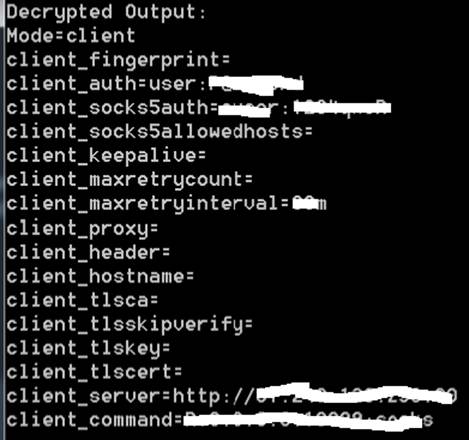

After running this script, we successfully retrieved the plaintext contents of blackwood.dll. conf. The decrypted output revealed multiple key-value pairs governing the malware’s tunneling behavior in client mode. A key indicator was client_server=http://[redacted]:80, which identifies the C2 endpoint, the malware connects to for command and control. This, along with flags such as client_socks5auth, client_proxy, and client_command, confirms that the malware functions as a remote-controlled tunneling client capable of proxying traffic or establishing covert channels over HTTP.

Figure 8: Decrypted config file

The use of an external RC4-encrypted configuration file allows the malware to decouple static logic from runtime behavior, making it harder for sandboxes or static analysis tools to quickly determine intent without full execution. Additionally, the presence of a hardcoded RC4 key string “My name is Blackwood !" serves as both an internal debug marker and a distinctive signature that links this sample to a broader tooling infrastructure likely reused across different campaigns.

These findings validate the earlier decoding work and complete the analysis chain, from static obfuscation to runtime decryption, to full configuration reconstruction. With this knowledge, we can now create targeted detection rules based on RC4 key indicators, file naming patterns such as .dll.conf, decoded parameter structure and known C2 endpoints.

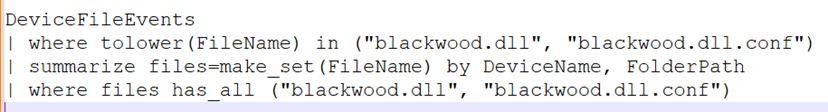

1. Detect blackwood.dll and blackwood.dll.conf in the same directory.

Figure 9: EDR query

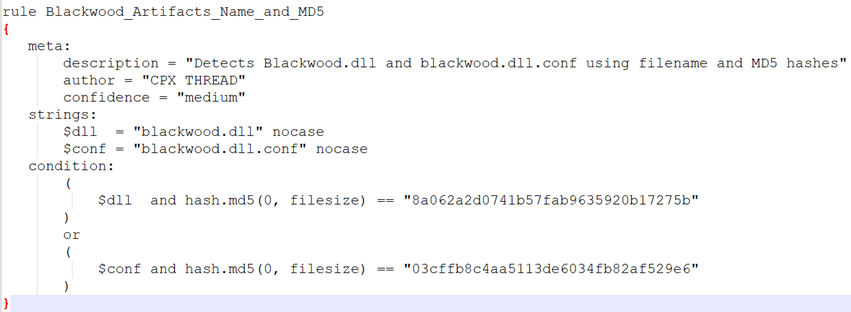

2. YARA Rule – YARA rule detects known Blackwood artifacts by combining filename and MD5 hash validation for both the DLL and its associated configuration file.

Figure 10: YARA rule

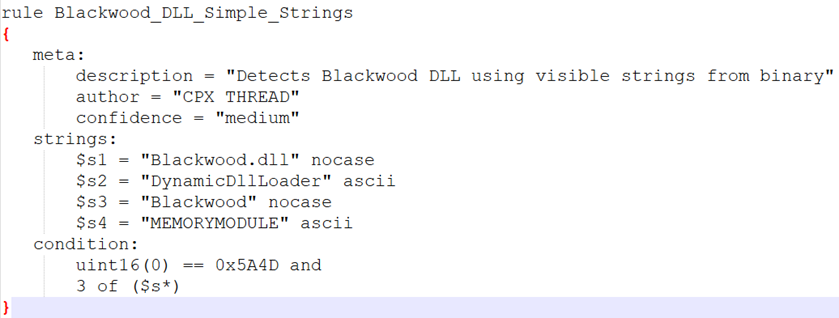

3. YARA Rule – YARA rule detects the Blackwood DLL based on multiple unique strings observed directly in the binary, including its loader component and in-memory module handling logic.

Figure 11: YARA rule