19 February, 2026

The .NET framework, widely used for legitimate Windows application development, has also become a prime tool for attackers crafting stealthy and adaptable malware. Its built-in features such as reflection, dynamic compilation, and memory management make it attractive for building loaders, stealers, RATs, and even destructive payloads.

This two-part blog explores how .NET malware works, how to analyze it effectively, and how to extract and reverse-engineer malicious logic from real-world samples. In this first part, we are covering foundational knowledge of malware built using .NET and a high-level walkthrough of the blackwood.dll sample. Part 2 will dive deeper into this same malware sample external configuration and runtime behavior.

The .NET threat landscape continues to expand, as attackers exploit its flexibility and integration with Windows environments to develop a wide variety of malware. Over the years, numerous threats have emerged that are built entirely on .NET. Additionally, this framework is also widely used to build loaders which silently deploy second-stage payloads in stealthy multi-phase attacks.

Common malware types leveraging .NET include:

To effectively analyze .NET-based malware, it’s crucial to understand how .NET executables operate under the hood. Every .NET malware sample, no matter how obfuscated, must follow the same core execution model defined by the framework. Understanding this flow helps malware analysts pinpoint where payloads may be hidden, how execution is triggered, and where to intercept behavior.

When a .NET executable file is launched, the Windows loader first parses the PE (Portable Executable) header, which then hands over its control to the Common Language Runtime (CLR). The CLR loads the assembly code, processes metadata, and reads the MSIL (Microsoft Intermediate Language) code. This MSIL is converted into native code at runtime using the Just-In-Time (JIT) compiler. It’s during this stage that many of the malware’s features come to life, executing actions that were only stored as instructions before, making them visible only when the program is running.

.NET malware often uses a combination of the following techniques:

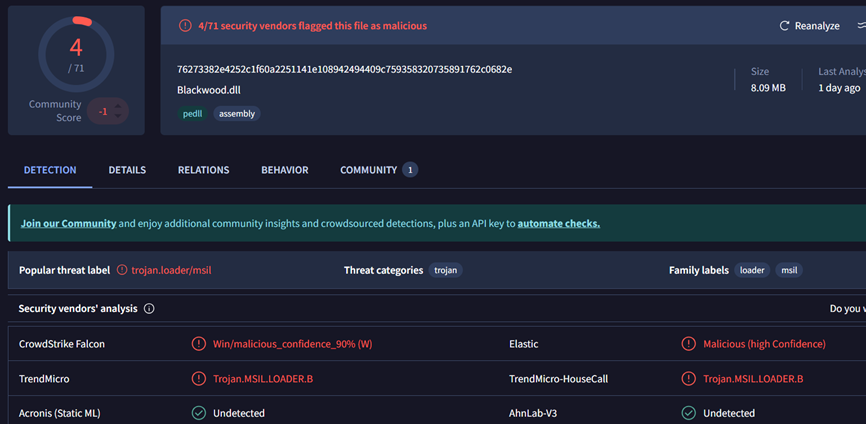

To illustrate these concepts, we turn to a real-world sample: Blackwood.dll and its companion encrypted configuration file (blackwood.dll.config), collected during our IR engagement on one of our clients. These files were dropped alongside a legitimate executable acting as a loader. While the loader appeared benign, behavioral clues pointed to the DLL as the true malicious component, making it the focus of static inspection. Notably the DLL has been available on VirusTotal since May 2025, it remains detected by only four vendors, underscoring how well it evades traditional AV signatures.

Figure 1: VirusTotal detection of the file

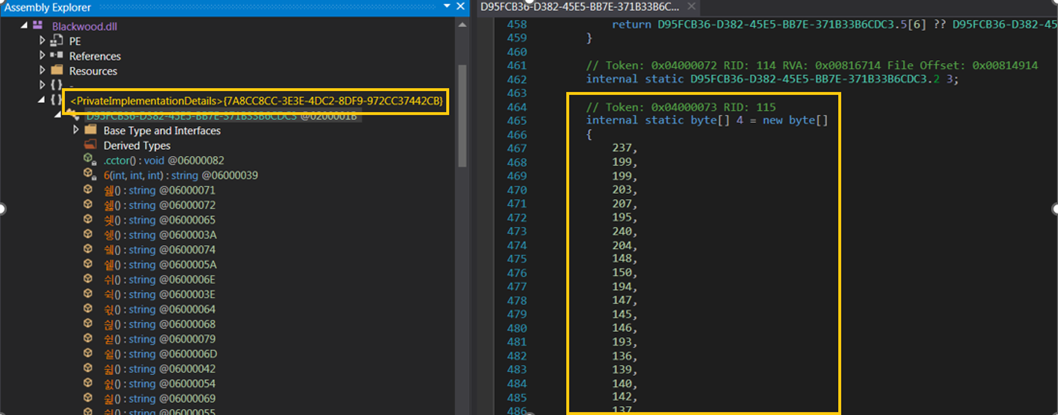

Opening the file blackwood.dll in the dnSpy tool immediately revealed signs of heavy obfuscation:

At first glance, ‘PrivateImplementationDetails’ may look harmless, it is normally created automatically by the C# compiler to store constants or fixed buffers. But in malware, this mechanism is deliberately abused. The malware stores all important strings inside one huge byte array and rebuilds them only when needed. Nothing human-readable exists in the binary until the program is running, which makes static inspection significantly harder.

This achieves several objectives:

Recognizing this pattern gives malware analysts an important lead that a .NET assembly is hiding something malicious. In benign programs, PrivateImplementationDetails is small, and compiler generated. But in the Blackwood sample, this class balloons into thousands of bytes, packed with hidden configuration data.

By tracing the helper methods that reference it, analysts can replicate the decoding logic in a standalone script to dump the full set of hidden strings for further inspection.

Figure 2: ‘PrivateImplementationDetails’ namespace contains long byte array

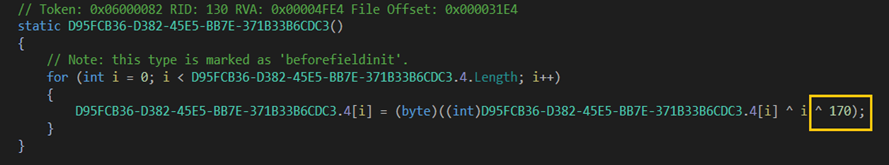

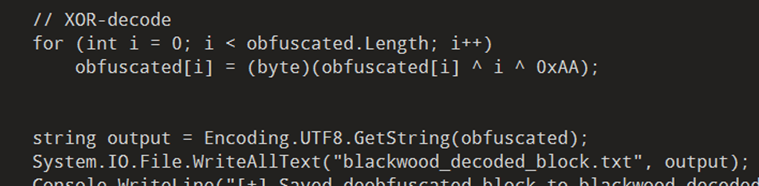

After inspecting the malware code in dnSpy, we located the decoding routine for the long byte array found in ‘PrivateImplementationDetails’, which holds the obfuscated data. This loop reveals how obfuscation works:

Figure 3: XOR key

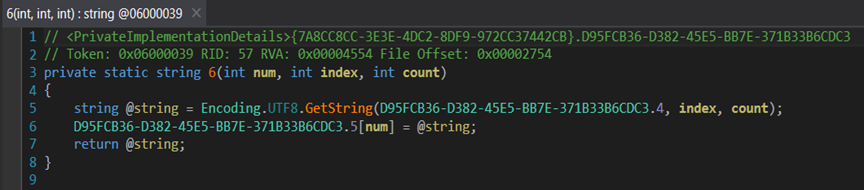

After this routine coded in the malware executes, the array then contains meaningful data (strings, config values) instead of garbage bytes. From there, helper functions like 6(int num, int index, int count) slice out sections of the array and convert them back into human-readable text:

Figure 4: String decryption function

UTF-8 is a common text format used by computers. UTF-8 encoding is the process of changing letters into numbers using this format so they can be stored. The numbers in this malware byte array were created using UTF-8 encoding, so we must use UTF-8 to convert them back into the correct readable text. If a different encoding is used, the output will show the wrong characters or unreadable symbols.

To get the hidden strings, we wrote a small C# script that copies the same decryption steps used by the malware. We ran this script on our analysis machine to safely convert the obfuscated byte array into readable text, without executing the malware itself.

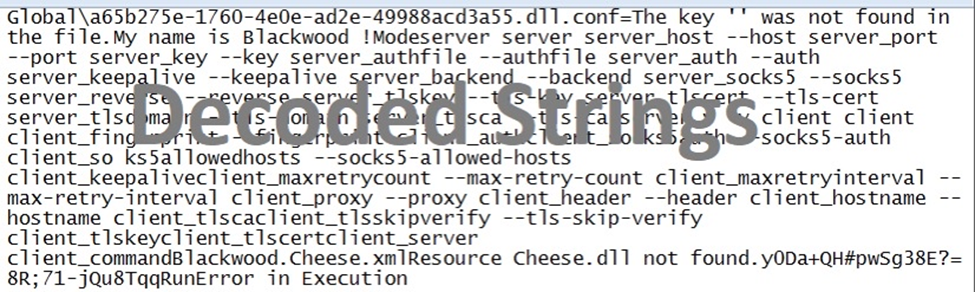

Figure 5: Script snippet to decode array

Once the obfuscated byte array was successfully decoded, it revealed a plaintext configuration structure resembling command-line arguments, including --host, --key, --authfile, --tls-cert, and others commonly used for proxying or tunneling connections. This configuration strongly resembles tools designed for encrypted C2 communication or reverse proxying and appears modular in nature indicating support for multiple execution modes (e.g., server/client). A notable discovery within the decoded content was the string "My name is Blackwood !", serving as an internal debug message or potential campaign marker embedded by the malware author. This reinforces the attribution to the broader tooling used by the Blackwood APT group and confirms that static de-obfuscation of the embedded byte array already reveals what the malware is built to do.

Figure 6: Decoded strings

With these strings now exposed, we gain a clearer picture of the malware’s runtime behavior, including how it assembles parameters for execution. More importantly, this stage of analysis uncovers the foundation needed to decrypt the external configuration file — a file encrypted using RC4 and loaded dynamically at runtime.

In Part 2, we will break down the decryption process, show how the key is identified, and how to decrypt the malware configuration file.

If you’d need support applying these methods to real incidents, please get in touch with our Digital Forensics & Incident Response team or explore our Threat Intelligence Services.